We’re more than halfway through the second-quarter corporate earnings season. And while the results for US companies show corporate growth, it’s been slower than normal—even the last few years’ normal. For the last four years, the “surprise percentage” of the S&P 500—the percentage by which all companies beat analyst expectations this quarter—has been 7.0% at the end of earnings season. Right now, it’s at a measly 2.3%. By this measure at least, that makes this one of the softest earnings seasons since 2008.

What’s going on? With pressure on China, cash flowing out of emerging markets, and continuing tensions in Europe, no one’s surprised things are sluggish right now. However, a small but prominent group of CEOs, investors, and economists suggest that this isn’t temporary, but the start of a completely new era of slower growth. Here are their reasons.

1. The cost of resources is rising

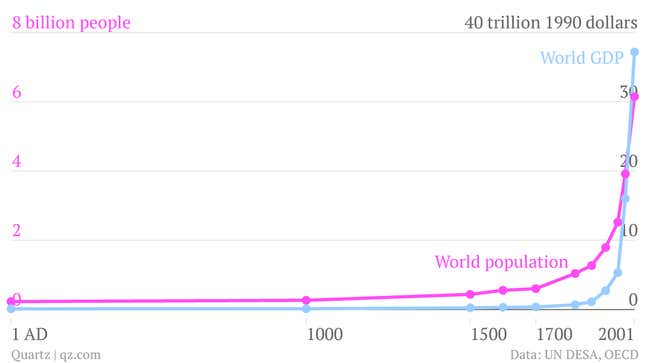

As the chart above shows, the global population grew by more than 50% from 1973 to 2009. The UN predicts that the population—and, as a consequence, demand for goods—will continue to rise.

Jeremy Grantham, the head of investment management firm GMO, is credited with accurately predicting every major stock market bubble for the last few decades. Now he believes resource scarcity will force our civilization to face “the race of our lives.” In his April quarterly letter to investors (pdf), he argues, “Our global economy, reckless in its use of all resources and natural systems, shows many of the indicators of potential failure that brought down so many civilizations before ours.”

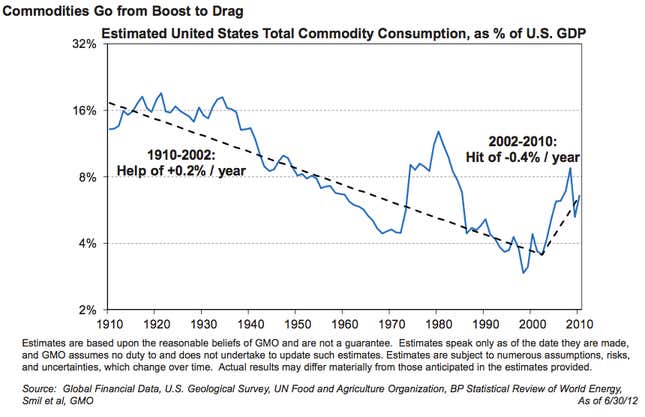

High demand and thus a high cost of resources are already causing a drag on global GDP, Grantham says. For example, for years, technological advances that allowed us to extract commodities from the Earth caused the price of manufacturing inputs to decline. That trend could be over.

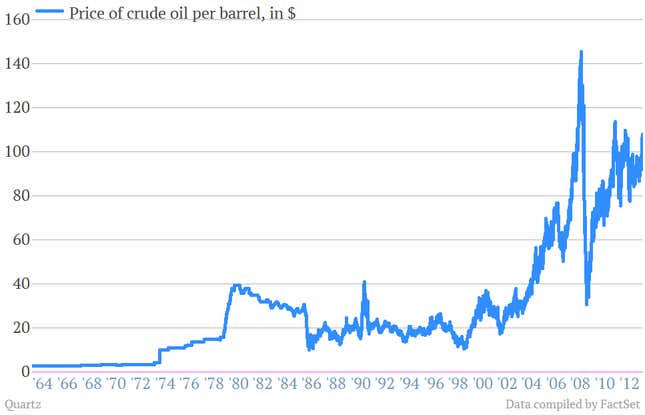

And in Grantham’s view, the price rise of commodities in the 2000s isn’t at all like (pdf) the one that happened in the 1970s (see his chart above), which was driven mostly by geopolitics. Oil companies, he believes, aren’t rolling in cash, even though price increases have brought oil from $14 per barrel in 1968 to $35 in 2000 to more than $100 today (all these in 2012 dollars). “[Price increases] are cost driven,” says Grantham. “The same applies, I believe, to most metals […] Even agricultural costs have soared, as fertilizer and fuel costs doubled or tripled and the costs of pumping water and a host of other lesser inputs leaped upwards.”

Fred Smith, the CEO and founder of FedEx, has made a similar argument—albeit less broad—about the rising cost of oil, which is the reason, he believes, that the pace of global trade is slowing. Businesses cut back on air cargo, cargo ships move slower to save on energy, and the interchange of goods slows down.

Moreover, continued economic stagnation produces new barriers to growth. It “could encourage protectionism across the various economic blocks,” John Coustas, CEO of Greek shipping giant Danaos, has warned in an interview with PwC. Higher costs of trade may slow down the spread of goods, concentrating them regionally rather than globally.

For his part, Grantham predicts that fracking and natural gas will end up producing cheaper energy, which will give the economy a 0.3%-0.5% boost over the next new years. However, that’s not enough to slow the rise in costs of all resources in the long run.

2. The world’s labor force is peaking

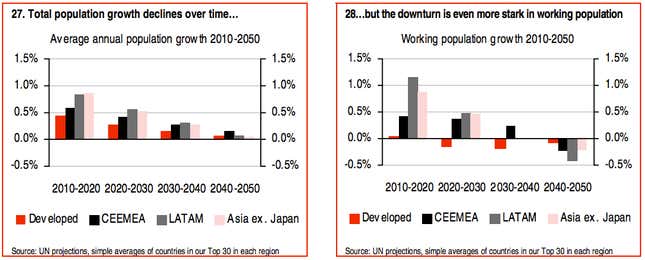

Part of the reason that the world’s economy has blossomed over the last few centuries is that more workers have been producing more goods. But now the world’s population is no longer increasing as quickly (pdf). As workforce growth declines in the next 20-30 years, workers will have to produce more and more in order to keep up the pace of growth we’ve become accustomed to.

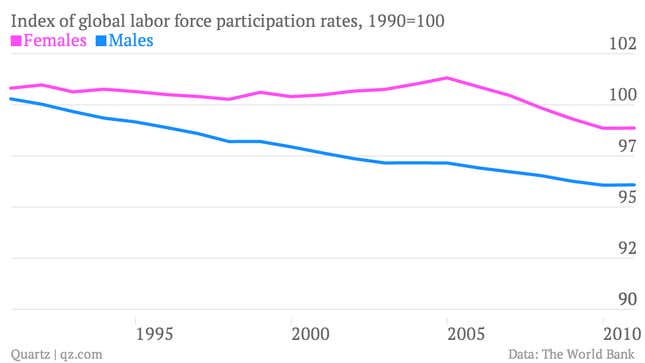

And for the last 50 years, Grantham points out, it’s been particularly easy to grow the workforce because women have been joining it in droves across the world. That trend is ending. Though there’s still room for female workforce participation to grow in some countries, globally the percentage has remained pretty much flat over the last 20 years, and the percentage of men has declined.

With fewer workers, each will have to be increasingly productive for the global economy to keep expanding at the pace it has during the last hundred years. It’s not clear that this is possible, because of the third reason:

3. There’s no technological game-changer

From cellphones to the internet, advances in communications technology have allowed for quicker dissemination of ideas and the faster development of new ones. But now that everyone can talk to everyone else, it’s hard to visualize the next big shift.

“The Internet is now a mature technology,” Coustas told PwC.” And as I look around today—and perhaps three years out—I really don’t see anything that might has [sic] the potential to drive change to the same degree that the Internet did in its formative stages.”

Pierre Azoulay of MIT and Ben Jones of Northwestern University found that the total productivity of a worker in research and development in the year 2000—the technological benefit she provides to the economy through innovation—was just 15% (pdf) of what it was in 1950. Not to mention that there may be fewer such researchers when the working-age population begins to decline.

It seems clear that new technologies will be developed in the future. But at what rate?

4. We’ve got climate change to deal with

Deny it at your own risk, but rising seas and more devastating storms could pose the deepest threat to the global economy. Business leaders are already frightened.

“Increasing climate damage, reflected mainly in food prices and flood damage, is going to increase. With any luck this will not be severe before 2030 (we allow for a 0.1% setback) but it is very likely to accelerate between 2030 and 2050. A great deal will depend on our responses,” writes Grantham.

There are varying estimates of the damage. A study last year suggests that climate change is already costing the world $1.2 trillion per year, or 1.6% of global GDP. Another in 2009 argued that climate change could lower the GDP of the typical poor country by 0.6%—which extrapolates to 40% by 2099. That research—based on current climate data—suggested that rich countries are better able to adapt to climate change, and might not see this damage.

Slower global growth is not necessarily a bad thing, particularly if it’s caused by something as simple as slowing population growth. Indeed, Grantham at least sees this as a gift that could preserve modern civilization. Taken separately or together, however, these developments could be enough to bring us to a new normal—permanently.

Clarification: Numbers from Factset mentioned in the first paragraph were amended to more accurately reflect Factset’s methodology and updated to reflect earnings from the US morning of August 1. The surprise percentage of any given stock is the percentage by which it beats analyst estimates of its earnings. So if analysts predicted that a stock would report earnings per share of $1.05 and they actually reported earnings of $1.20, then the surprise percentage would be ($1.20-$1.05)=14.3%. Factset aggregated this data across all companies in the S&P 500.